Milk can label diary

Posted on March by Jon Isaak

This is a page from Anna Baerg’s 1922 diary written on milk can labels.

This is a page from Anna Baerg’s 1922 diary written on milk can labels.

A hundred years ago, MCC sent relief aid, including food, to Ukraine during the time of the Russian Revolution and civil war. It was the reason MCC was organized: to bring North American relief aid to those suffering in Ukraine.

A young woman by the name of Anna Baerg wrote her diary on the only paper she could find, repurposing the fronts and backs of milk can labels (several hundred) to write her experience of the wartime conflict in Ukraine.

CMBS has these labels in its collection (https://cmbs.mennonitebrethren.ca/personal_papers/baerg-anna-1897-1972-2/). And they have been translated into English and published as a book (https://www.commonword.ca/ResourceView/82/1180).

The milk can label diary is a testament both to the compassion/action of the faith community and the resourcefulness/resilience of individuals like Anna Baerg.

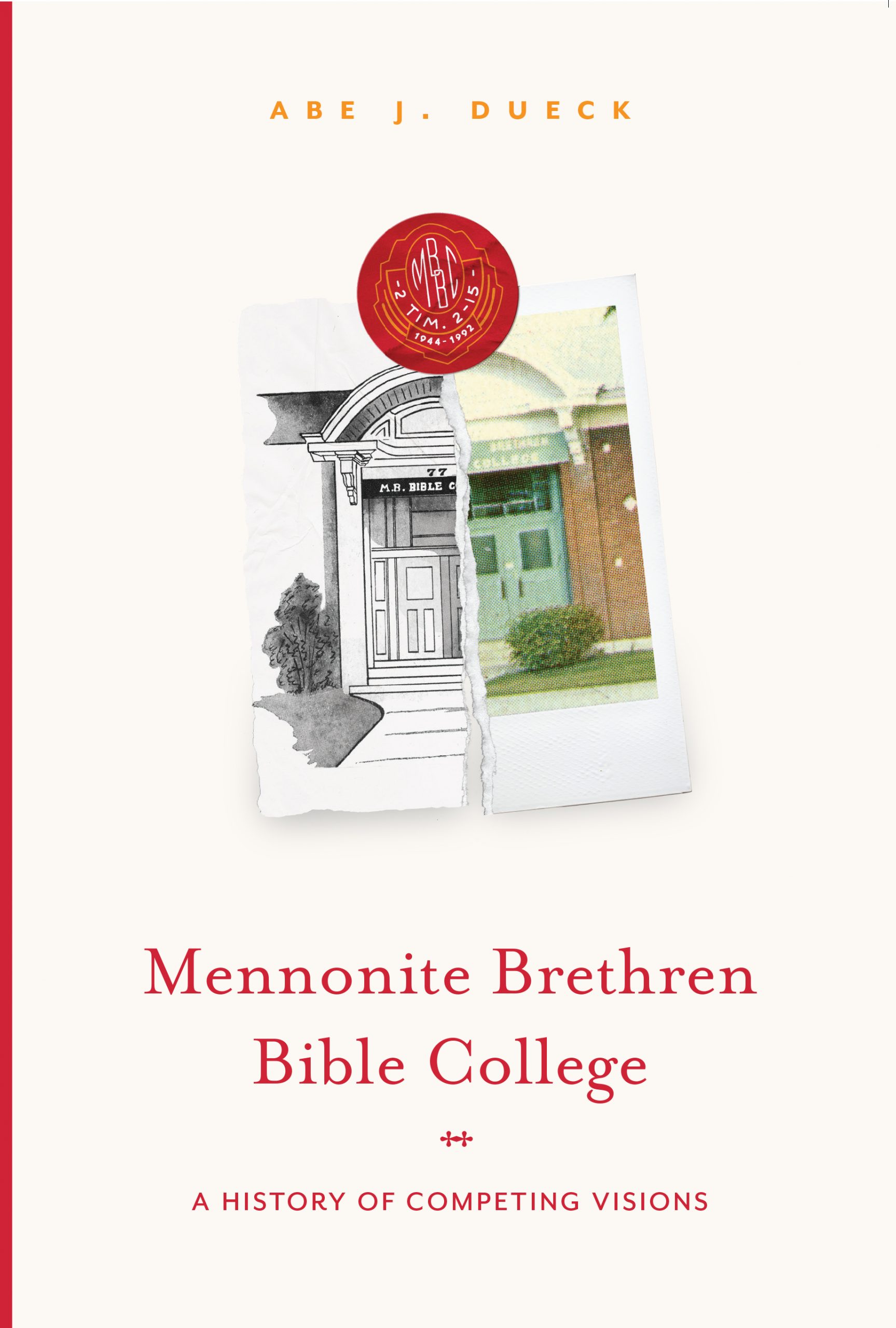

MBBC History Published

Posted on by Jon Isaak

The Mennonite Brethren Historical Commission’s most recent publication is Abe J. Dueck’s book, Mennonite Brethren Bible College: A History of Competing Visions. The book—released by Kindred Productions in April 2021—documents and assesses the Canadian Mennonite Brethren church’s education agenda from 1944 to 1992, a story of competing visions. To purchase your copy, see https://www.kindredproductions.com.

The Mennonite Brethren Historical Commission’s most recent publication is Abe J. Dueck’s book, Mennonite Brethren Bible College: A History of Competing Visions. The book—released by Kindred Productions in April 2021—documents and assesses the Canadian Mennonite Brethren church’s education agenda from 1944 to 1992, a story of competing visions. To purchase your copy, see https://www.kindredproductions.com.

Dueck was awarded one of the Historical Commission’s MB Studies Project Grants in 2016 for his research project on the history of the Mennonite Brethren Bible College. The focus of his research was the guiding vision of MBBC as it was conceived in the early 1940s and as it evolved and became an issue of intense disagreement and conflict through the years.

MBBC was the main program supported by the Canadian Mennonite Brethren conference during the college’s existence (1944–1992), and, as such, its story is also in large measure the story of the conference as a whole. The theology, worship, and polity of the conference are reflected in the discussions and the often heated debates that transpired from year to year concerning the nature of the college. Now, five years later, Dueck’s research has been published.

The main sources of information used by Dueck are the detailed reports and minutes of the college boards or committees (later Board of Higher Education), the proceedings of the Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches, and the administrative and faculty minutes and related documents. In addition to these, he consulted other documentary sources, such as reports in denominational newspapers and magazines, letters, college catalogues, yearbooks of convention proceedings, biographies, and autobiographies.

Dr. Abe J. Dueck is academic dean emeritus of Canadian Mennonite University in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He was born in Coaldale, Alberta, and studied at various institutions, including MBBC, the University of British Columbia, and Goshen Seminary. In 1971, he received his PhD in religion from Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

MBBC was not the end of the story of Mennonite Brethren higher education in Canada. The institutions that followed (Concord College and Canadian Mennonite University) developed in ways that took into account and built on many of the experiences, characteristics, and strengths of the founding colleges, including MBBC.

Dueck taught at MBBC for 23 years and served as academic dean for 15 years.

To view the CommonWord book launch on June 17, 2021, see https://youtu.be/379iCgJ5ZjE

Abe Dueck, one time faculty and academic dean, deserves wide recognition for his courage and candor. His study of the Mennonite Brethren Bible College will be of interest to anyone familiar with the once flag-ship denominational center. As the title implies, throughout its history, the school struggled to find an identity acceptable to its supporting constituency, itself subject to a constantly shifting cultural milieu. Baffling for administrators and faculty alike was finding a healthy balance between theology and liberal arts or conceptualizing an acceptable divide between undergraduate and graduate offerings. Often surfacing in this study is the tension confronting the college in fine-tuning a music culture that would attract constituency approval. Dueck’s meticulous study offers not only a compelling narrative of MBBC but also a skillful analysis of the issues that throughout most of its existence threatened the health of the college and ultimately caused its demise (David Giesbrecht, former librarian at Columbia Bible College, Abbottsford, BC).

In this thorough study of MBBC’s 48-year history, Abe Dueck reveals the enthusiasm Mennonite Brethren had for education, alongside their almost constant disagreement about what kind of education it should be. This is a story populated by dynamic and influential personalities, robust debate, debilitating tension, but also reminders of God’s gracious blessing on the school and of its enormous contribution to the life of the Canadian MB Church (Dora Dueck, author and former MB Herald editorial staff, Delta, BC).

Oral Interviews Digitized

Posted on September 25 by Jon Isaak

This is a group of women from the Mary Martha Home, posing for a 1926 photo in their uniforms (CMBS photo NP066-01-20 viewable at the Mennonite Archival Information Database).

Recently, I completed a media preservation project. It involved the digitization of audio recordings from analogue cassette tapes to digital mp3 files. In 1987, Frieda Esau Klippenstein interviewed 34 Mennonite women for an oral history project, documenting the experience of Mennonite domestics associated with the Mary Martha Home in Winnipeg. The interviews ranged from 60 to 75 minutes each.

The women—usually for a year or two, but some longer—had worked for wealthy Winnipeg families in their homes during the 1920s through to the 1950s—cooking, cleaning, and child minding. For many years, the women were under the supervision of Anna Thiessen (1892–1977), matron of the Mary Martha Home, a house at 437 Mountain Avenue and ministry of the Mennonite Brethren Church of Manitoba.

The Mary Martha Home functioned as an employment agency and living quarters for the women between or during jobs. It was also a place for the women to gather on Thursdays, when their employers gave them the afternoon off. The women were mostly young, new to the city, and from Mennonite immigrant/refugee families; they did what they could to help their families resettle in Canada.

When the Mary Martha Home closed in 1959, more than 2,200 young women had benefited from its services.

The digitization of the interviews ensures that researchers will be able to access all 34 interviews, even as the original cassette tape recordings deteriorate with time.

Below is a 3-minute excerpt from Frieda Esau Klippenstein’s interview with Agatha Isaac in 1987.

https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/756

For more information about the Mary Martha Home and the ministry of Anna Thiessen, see the links below.

- The GAMEO article on the Mary Martha Home,

https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mary-Martha_Home_%28Winnipeg%2C_Manitoba%2C_Canada%29 - The MAID photo collection of the Mary Martha Home,

https://archives.mhsc.ca/mary-martha-home-photograph-collection-4 - The online version of Anna Thiessen’s memoir, https://archive.org/details/TheCityMissionInWinnipegOCRopt

5 Online Research Resources

John M. Schmidt (1918–2008), one of the early MB radio preachers, recording a Gospel Light Hour broadcast in the early 1950s from the Logan Ave. (MB) Mission Church, Winnipeg. He recorded after 10 pm to avoid traffic noises. Photo credit: MAID CA CMBS NP191-01-74.

My COVID-19 adaptation in March and April has been to work from home—writing file descriptions, scanning photos, editing encyclopedia articles, and updating the websites I manage. And I still go to the archives each week. I work alone, so physical distancing at the archives is not difficult; but, yes, CMBS is closed to the public, until further notice.

Since many are spending more time online these COVID days, I have been promoting the many Anabaptist-Mennonite online resources available for historical research; I’m thinking of five in particular.

For example, I finished scanning the 112 images in the John M. Schmidt photo collection—he is one of the Mennonite radio broadcasters that David Balzer wrote about in the March 2020 Mennonite Historian, now online at (1) the Mennonite Historian website, www.mennonitehistorian.ca/. And those photographs are now viewable online at (2) the MAID website, https://archives.mhsc.ca/john-m-schmidt-photograph-collection-2.

I also edited a biography of Schmidt for posting to (3) the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO) website, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Schmidt,_John_M._(1918-2008), and updated the file description for Schmidt’s personal papers fonds at (4) the CMBS website, http://cmbs.mennonitebrethren.ca/personal_papers/schmidt-john-m-1918-2008/.

And I scanned 16 additional Mennonite history books, uploading them to (5) the Internet Archive website, bringing the total to 96 e-books readable online, https://archive.org/details/@jonisaak.

That makes five different websites—accessible to researchers anywhere with internet service!

Looking for a baptism photo, obituary of a loved one, or a book, magazine article, or church decision on some theological issue—there are online research resources available and people like me who can help you find what you are looking for.

This is usable history, some of the best kind!

1950s Mennonite newspaper now viewable online

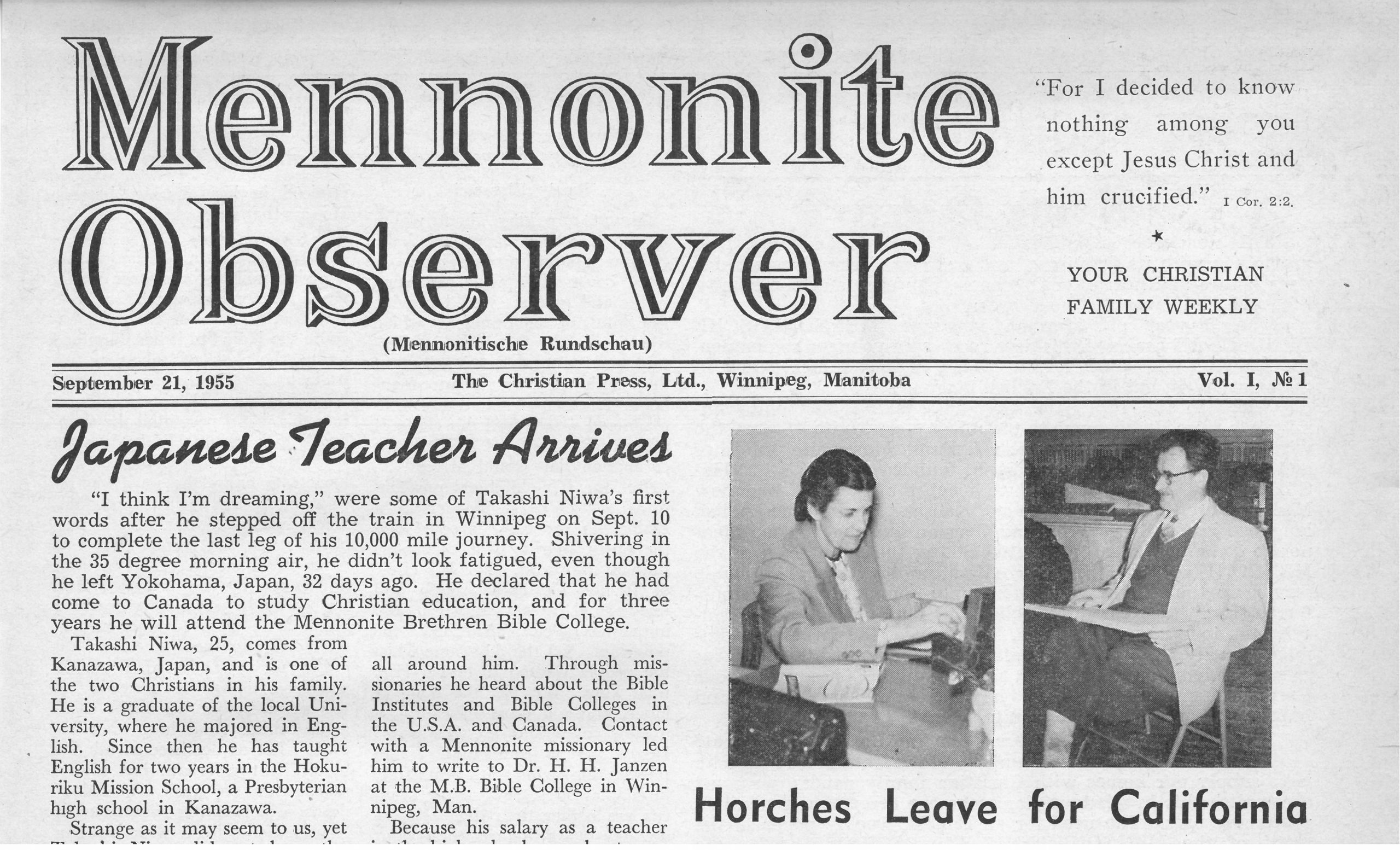

Pictured is an excerpt from the first issue of the Mennonite Observer, published on September 21, 1955. Modeled after Die Mennonitische Rundschau, the weekly Mennonite newspaper ran from 1955 to 1961.

The 12-page Mennonite Observer was published by The Christian Press in Winnipeg, Manitoba. As the language transition from German to English among Mennonites in Canada was intensifying, the English-language Mennonite Observer took the place of the Mennonite Brethren German-language Konferenz-Jugendblatt. Les Stobbe was the first editor of the Mennonite Observer, followed by Gerhard D. Huebert.

According to the masthead, the newspaper aimed “to have Christ at the helm, the salvation of man as its goal, and the essential unity of all true Mennonites as its guiding principle.” It was a newspaper with reports from Mennonite high schools and colleges in North America and beyond, missionary updates, congregational news, obituaries, and Bible-based devotional writings. The newspaper was designed to relate to people from a broad range of Mennonite conferences, even though its owners/editors were from the Mennonite Brethren Church.

The publication ceased in December 1961 and the Mennonite Brethren Herald took its place with a new mandate, starting in January 1962. The MB Herald became the official communication organ of the Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches, a publication which ran for 58 years; the final edition was printed in January 2020 (see post).

Thanks to the efforts of Susan Huebert (many hours of scanning!), all the issues of the Mennonite Observer are now viewable online. With the author index created by David Perlmutter, the church, mission, school, and community news from this era are now more easily accessible to researchers. For a description of the Mennonite Observer and links to each of the 351 issues, click here.

Discerning women in ministry leadership in the Mennonite Brethren church

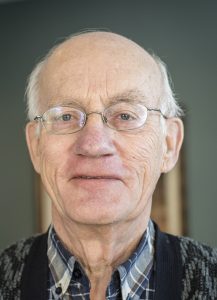

“It’s like a detective story; you see all these threads woven together,” says Doug Heidebrecht.

“It’s like a detective story; you see all these threads woven together,” says Doug Heidebrecht.

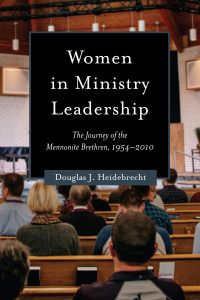

Heidebrecht’s Women in Ministry Leadership: The Journey of the Mennonite Brethren, 1954–2010 is the story of the denominational conversation regarding women in ministry positions within Canadian and U.S. Mennonite Brethren churches.

Women in Ministry Leadership was launched on May 10, 2019, at Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg, with some 45 people in attendance. It is a more popular presentation of Heidebrecht’s PhD dissertation, “Contextualizing Community Hermeneutics: Mennonite Brethren and Women in Church Leadership” (University of Wales, 2013).

Since the Mennonite Brethren General Conference gathering in 1999, he has been researching the paths Mennonite Brethren have walked regarding women in leadership roles even as the conference continued move in new directions leading to the 2006 Canadian conference resolution.

“No other issue has received this level of attention by Mennonite Brethren during the second half of the 20th century,” Heidebrecht writes.

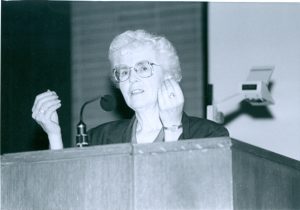

Katie Funk Wiebe speaks at General MB Conference convention in Winnipeg, 1990. MAID photo NP149-1-8662.

Women’s columns in MB periodicals during the 1960s gave women a public voice in the conference, and became the first avenue for engaging questions regarding women’s involvement in the church that were being raised within the larger society. Katie Funk Wiebe, in particular, was significant in calling for change not only through her prolific writing (articles and books), but also in her speaking and teaching ministry.

However, it was the unprecedented “spontaneous attendance” of five women – Irene E. Willems, Betty Willems, Mary Poetker, Kae Neufeld, and Anne Neufeld – as delegates at the 1968 annual Canadian MB convention that opened the door for increasing participation of women in conference gatherings and raised new theological questions for provincial and later national conferences, says Heidebrecht.

Heidebrecht explores three interwoven themes in the book.

- What does the Bible say?

- How does the church live faithfully in world that is changing?

- And how do Mennonite Brethren wrestle together as a community toward the seemingly elusive goal of consensus.

In the course of his research, Heidebrecht had many conversations with key participants in the study conferences and the formation of resolutions. However, the book is based on written materials – board meeting minutes, papers, and published articles.

The focus is not solely on official leaders – Heidebrecht also presents how people in church engaged in this conversation through correspondence and Letters to the Editor from the Mennonite Brethren Herald (Canada) and the Christian Leader (US).

“How do you give voice to the people in the pews?” Heidebrecht says the letters provided an avenue to bring those voices –of both men and women – into the book. He recognizes the sensitive nature of telling a story that is still unfolding where many participants continue to be actively involved in Mennonite Brethren churches and leadership roles.

Though his source materials are in the public record, Heidebrecht’s work makes the evidence accessible to readers by telling the story, highlighting the decision-making process, and interpreting the underlying currents all in one place.

“It’s a story that needed to be told,” says Jon Isaak, secretary of the MB Historical Commission, which commissioned Heidebrecht to update his dissertation research to 2010 and publish the book with Kindred Productions.

Heidebrecht wrote about the Canadian Conference 2006 resolution in a final chapter of the book, a component not included in his dissertation. “Have we remained in 2006?” one participant asked at the book launch. “What gives hope is local churches wrestling with their own convictions,” says Heidebrecht.

“This book gives a sense of the story, the push and pull, frustrating and fascinating dimensions,” says Isaak.

This article was written by Karla Braun for MB Herald and was posted on May 15, 2019. See https://mbherald.com/wiml-journey/

Anna Janzen Neufeld diaries donated

Summer 2018 marked a significant accession at CMBS. Hildegard (Peters) Isaak (b. 1933), granddaughter of Anna (Janzen) Neufeld (1868–1945), donated Anna’s original diary/journal books to CMBS (Acc. no. 2018-08). See image showing Anna’s diary/journal books.

Summer 2018 marked a significant accession at CMBS. Hildegard (Peters) Isaak (b. 1933), granddaughter of Anna (Janzen) Neufeld (1868–1945), donated Anna’s original diary/journal books to CMBS (Acc. no. 2018-08). See image showing Anna’s diary/journal books.

In addition to the donation of the diaries, transcriber and translator Peter Neudorf (b. 1935) of Vancouver donated digital copies of his German transcriptions and English translations of the family letters and Anna’s diary/journal books at the same time.

Peter spent about nine years on the transcription/translation project, starting in 2009. Peter’s wife Helga (Peters) Neudorf (1937–2017), another of Anna’s granddaughters, edited and proofread Peter’s translations until Helga’s passing. Grandson Helmut Peters (b. 1935) also helped with translation verification. Hedy (Peters) Pletz (b. 1942) is also a granddaughter. The original family letters remain in the possession of the family.

The donated collection at CMBS includes 30 cm of textual materials: 6 diary/journal books, 1 notebook, 1 friendship autograph book, and 744 pages of transcriptions/translations (i.e., English translations of some 70 letters written by Kornelius A. Neufeld (1869–1917) dated from 1890 to 1917, as well as English translations of Anna’s diary/journal books dated 1916 and 1919 to 1925). (See the online description at http://cmbs.mennonitebrethren.ca/personal_papers/neufeld-anna-janzen-1868-1945/.)

Through letters and journal entries, the collection documents well the life of a Mennonite factory family as they experience loss due to the Russian Revolution and First World War, emigration from Ukraine, eventual liquidation of their assets, and the challenges of starting life over in a new country.

Anna Janzen was the daughter of industrialist Jacob Wilhelm Janzen (1845–1917) and Helena Unrau (1847–1917). Anna was born in Andreasfeld, Chortitza, on June 23, 1868. She married Kornelius Neufeld on June 26, 1891, in Serjejewka, Fuerstenland. They had eight children, two of whom died in infancy. Kornelius Neufeld was the son of Abram A. Neufeld (1820–1876) and Helena Unrau (1834–1898). Kornelius was born on May 26, 1869, at the Neustaedter Estate, located between Einlage and Ekaterinoslav, where his father Abram worked as a miller. His father died in 1876 of diabetes in Steinfeld Schlactin, a new farming settlement to which they had moved. Their 135-acre farm was sold for 50 rubles and the family sent back to where they had come from. Some years later, in 1889, Kornelius’s older brother Herman took him to Serjejewka, Fuerstenland, where Kornelius started to work in the Janzen-Klassen farm implement foundry. In 1891, he married the Janzens’ daughter Anna and was eventually promoted to management of the factory. After the Janzen-Klassen partnership broke up, Kornelius and his father-in-law formed a new foundry and machine shop.

About his translations, Peter writes, “I began the translation project with about 70 letters, the first one written by Kornelius in 1890 to his brother Herman in Nikolayevka. Starting in 1916, his wife, Anna Janzen, kept a diary, writing almost daily. She produced eight journal books in total; two were destroyed. For the first diary (321 pages) and the letters, I transcribed the text from Gothic script to English script and then translated the transcription into English. Eventually, I translated directly from Gothic to English. I started the project in 2009 and sent the first letter translations for the family—Helga’s siblings—to read on December 28, 2009, and the last one on August 11, 2018.

“Having been a technician with IBM for over 30 years, the word can’t was rarely in my vocabulary. On occasion, I would spend up to three days on a particularly difficult word, that is, a couple of hours a day, and then I typically came up with an English translation. Some Ukrainian words I could not transpose and I left them as Ukrainian. I want to give credit to my wife, who, as long as she was able, proofread and corrected my grammar. I thank Helmut Peters, her brother, for taking over after her passing.

“Anna’s diary accounts give evidence of enjoying incredible wealth and then of experiencing the total loss of everything following the Russian Revolution. There is the narration of her husband’s appendicitis operations and ultimate death in 1917. The family, minus father, managed to flee to Germany on November 23, 1918, from their large home on the factory compound, travelling by train with the retreating German soldiers following the end of the First World War. Then there is her daughter’s death—also of appendicitis—after needing to be left in Halifax as they immigrated to Canada in January 1922 following a three-year stay in Germany. Also moving is the humbling experience of having to live by gifts from kind-hearted Germans when the family’s money ran out and Germany faced massive inflation.

“Anna was clearly a person that always needed people around her. Her diary describes many visits with friends, and yet there are regular expressions of loneliness. Still, the message that comes through almost daily in the entries is her conviction that God cares and will provide.”

This accession report by Jon Isaak (Anna’s great-grandson) was first published in the Mennonite Historian 44/4 (Dec. 2018): 7.

The Russian Mennonite Story

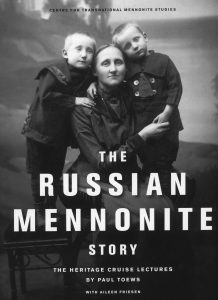

Released in April 2018, The Russian Mennonite Story: The Heritage Cruise Lectures is a book documenting Prof. Paul Toews’s long-standing contribution to understanding better the Mennonite experience in Russia. Toews was well known for guiding Mennonite Heritage cruises to Ukraine before his passing in 2015. Dr. Aileen Friesen edited Paul’s cruise lectures for the book. CMBS was responsible for making high-resolution scans of over 40 photographs from its photographic collection for reproduction in this book. The book sells for $39 and is available at https://www.therussianmennonitestory.com/.

Released in April 2018, The Russian Mennonite Story: The Heritage Cruise Lectures is a book documenting Prof. Paul Toews’s long-standing contribution to understanding better the Mennonite experience in Russia. Toews was well known for guiding Mennonite Heritage cruises to Ukraine before his passing in 2015. Dr. Aileen Friesen edited Paul’s cruise lectures for the book. CMBS was responsible for making high-resolution scans of over 40 photographs from its photographic collection for reproduction in this book. The book sells for $39 and is available at https://www.therussianmennonitestory.com/.

Below is a book review written by Peter Epp, Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg.

In The Russian Mennonite Story: The Heritage Cruise Lectures, Dr. Paul Toews’s three Heritage Cruise lectures are set alongside vivid photographs of Mennonite life—past and present—in Russia (now Ukraine).

While the book is surely welcomed by former Heritage Cruise members for providing a reminder of their tour—Toews gave the lectures during the 16 years he accompanied the Mennonite Heritage Cruise (1995–2010) down the Dnieper River into the heart of the former Mennonite homeland—its impact will extend much farther. Its bold use of large, stunningly (sometimes shockingly) high resolution photographs allows it to serve as a virtual tour for those who have never taken the tour.

Toews never had a chance to finish or publish his lectures—he died in 2015. However, Dr. Aileen Friesen agreed to edit, complete, and gather photographs for the production of a published version of Toews’s lectures. The result is a well-organized, easy-to-follow presentation. The Russian Mennonite Story is a worthy addition to the growing catalogue of introductory Russian Mennonite history books that serve those who want pass their story on, quickly review it, or discover it for the first time.

Toews’s three lectures mostly proceed in chronological order, with each section adding another layer of interpretation. The first lecture, “Power and Promise,” describes the arrival and pre-First World War life of Russian Mennonites, emphasizing their relatively rapid rise to economic success and cultural confidence. Here, Toews asserts that traditional assumptions of Mennonite simplicity are themselves too simple. Rather, Mennonites were “emulat[ing]…the industrial elites of Western Europe and America” quite successfully (34).

The second lecture, “Pathos and Tragedy,” describes the horrors that followed the First World War, as Mennonites suffered through that war, the Bolshevik Revolution, the resulting civil war, and Soviet oppression. Toews uses the lecture’s title to explain how contemporary Mennonites might understand this part of their story. On the one hand, their suffering was the result of them being victims to an external pathos, which Toews asserts to be a kind of madness that overtook the understandable goals of the early revolution. On the other hand, their suffering was the result of Mennonites’ tragic choices—hard decisions that Toews suggests were “the lesser of two evils” or had hidden consequences—that can be both pitied and admired (64).

The third lecture, “Paradox and Irony,” provides a concluding interpretation of the first two lectures and subsequent events. Here, Toews asserts that the Russian Mennonite experience can be understood through the lenses of paradox and irony: a move to Russia for preservation produced radical innovation, a German identity that provided stability later led to displacement, a search for permanence later produced exile, significant Mennonite innovations eventually “drew attention to…‘foreignness’” (77), and an attempt to preserve a free church led to a Privilegium that produced something of a Volkskirche (people’s church). To conclude, Toews suggests that the most significant irony is one of Mennonite resilience: the Soviet attempt to “consign [Mennonites] to the ash of history” has recently given way to a reclamation of the Mennonite story by Mennonites and non-Mennonite Ukrainians.

Finally, Aileen Friesen (who also provides a preface) completes the book with a necessary conclusion of her own, carefully suggesting that Toews’s narrative, while foundational, will benefit from the natural historiographical process of engaging “fresh approaches and challenge[s].” Friesen outlines many of these, including the need for more social history, which could tell us more about Mennonite women, everyday lives, and Mennonites’ connections to non-Mennonite neighbours. She also notes that Toews’s narrative will benefit from further research on Russian Mennonite colonialism and class, research that challenges the traditional Mennonite narrative. Toews’s interpretive use of pathos and tragedy limits a more complete understanding of Mennonite accountability and the portrayal of current Mennonite humanitarian aid and Ukrainian attitudes towards Mennonites reflect a somewhat colonial tone.

Overall, however, The Russian Mennonite Story is not designed for nuanced historical debate, but to capture one of the foundational ways Mennonites came to tell this part of their story as they began to fully engage it. It does this eloquently and beautifully. Preserving this crucial, accessible piece of Toews’s work is a gift for generations to come.

This Book Review was first published in the Mennonite Historian 44/3 (Sept. 2018): 12.

Flight: Letters from the Mennonitische Rundschau, 1929/30

Posted on by Jon Isaak

Harold Jantz (standing with Neoma Jantz) addresses a group gathered in Winnipeg for the launch of his book, Flight, on Tuesday, April 10, 2018, at the CommonWord resource centre, Canadian Mennonite University. Photo credit: Steve Salnikowski, ChronicCreative.

In 2012, when Harold Jantz first came to the archives to borrow the bound collection of all the 1929 issues of the weekly magazine Mennonitische Rundschau (or Mennonite Observer in English), I was quite nervous. Why? It is a fragile and very rare collection. But as I learned more of what he had in mind, it seemed like a good risk to take.In fact, the Mennonite Brethren Historical Commission was so impressed with his translation project that it awarded him a project grant in 2015 (see news release at: http://www.mbhistory.org/news.en.html#dec_15_2015).

In this book, aptly called Flight: Mennonites facing the Soviet empire in 1929/30, from the pages of the Mennonitsche Rundschau (Eden Echoes Publishing, 2018), Harold has rehabilitated voices of suffering and longing from the past. How so? Harold translated and summarized all the German letters published in the Rundschau during the years 1929/30.

These letters were submitted and published with the hope that loved ones in North America or in Russia might learn the news of those family members who had emigrated or who had been blocked from emigration by Soviet authorities. The newspaper functioned as a “message board” for Mennonites separated from their loved ones by geographical and political barriers.

These letters—likely allowed by sympathetic Soviet officials—eventually arrived in North America and the recipients turned them over to the Rundschau editor, Herman Neufeld, who edited and published the letters out of his office in Winnipeg, Manitoba. While other newspapers carried news from Russia, the Rundschau carried the largest amount and was read by the largest number of people on both sides of the Atlantic.

Unfortunately, as often happens, a social group that manages to obtain liberation from oppression turns around and becomes a new oppressor. Such was the case following the Bolshevik revolution and civil war. And so it was that the Mennonite settler communities living in Russia got caught in this massive social and economic reversal.

The Soviets were passionate in their quest to remake Russia and the Mennonites were simply on the wrong side of Stalin’s grand Five-Year Plan. They were offside for three reasons:

- They professed a Christian faith.

- They practiced private landownership, even though they shared much in communal villages.

- The language of their literature, church life, and cultural preference had remained German in their farming settlements on the Russian steppes; now they were associated with Russia’s enemy, Germany.

Many felt they now had little choice other than to emigrate from Russia. However, most did not succeed. Thousands of Mennonite settlers assembled in Moscow, beginning in the summer and through the fall of 1929, requesting permission from Soviet authorities to leave. Some 5,600 German settlers—3,885 of whom were Mennonites—managed to secure exit visas through Germany, but more than 8,000 were refused exit papers and were sent back in hastily assembled boxcar trains to their villages or into exile. Many thousands perished.

Flight makes a huge contribution for three reasons:

- Harold uses one the best first-hand public sources for this period of terror and loss, the Mennonitsche Rundschau

- Harold puts into English these accounts, which would otherwise be inaccessible, as most North Americans no longer can read German very well.

- Harold has created an extensive Index of names, subjects, and places, so as to make this massive 735-page book usable.

Clearly a labour of love—readers with family ties to this era will be especially appreciative of this book, as will anyone interested in human rights, political science, sociology, church history, and Russian history.

Flight sells for $60 and is available through the CommonWord resource center on the campus of Canadian Mennonite University in Winnipeg. More information at: https://www.commonword.ca/ResourceView/2/19795?readmore=1

Written by Jon Isaak, Director of the Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies, Winnipeg.

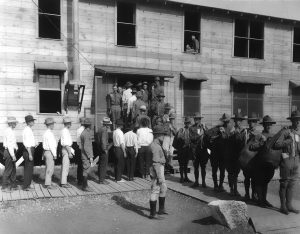

Remembering the flight from Oklahoma

Drafted American men reporting for WWI service at Camp Travis, San Antonio, Texas (1917-1918). Photo credit: American National Archives, 165-WW-474B-1.

In 2018, our Klaassen family [Roger Epp, the author, is speaking about his family] will mark 100 years since my grandfather, his brothers, and their father arrived in Canada. We can easily take our family story for granted, something so well-rehearsed that it contains no more surprises. Or we can treat it as a kind of Heilsgeschichte, the salvation history of a faithful remnant, set apart, when instead it really discloses so much of what still makes for suffering in our world—if no longer for us, then for others.

Our Klaassen story is not just our story. It is inseparable from the story of war, nationalism, dispossession, and migration. We should resist the urge to sentimentalize or limit its reach in our own times, especially after a U.S. presidential election that unleashed the kind of menacing anti-foreigner rhetoric our people and others experienced at the outset of World War I.

Now, of course, we have blended comfortably into mainstream North America. We are not a threat to anyone. But we once were. In the country where our family landed in 1884, in a harbour watched over by the Statue of Liberty, the minds and bodies of Mennonite sons would be subjected to intense and brutal forms of abuse within a generation. Not all of them survived.

Because the Klaassen family is unusually rich in memoirs, diaries, and other documents, as well as the retellings at reunions, the outlines of the Klaassen family’s quarter-century in southwestern Oklahoma and then our flight to Canada are familiar enough.

We know that Jacob Klaassen (1867–1948), my great-grandfather, claimed land near the Washita River, as did his brother and his mother Maria, born in what is now Poland and widowed on the Great Trek to Central Asia. He married Katharina Toews (1871–1908) from Kansas, built a farm, and preached in the Herold Church in the country, in whose cemetery his wife, an infant daughter, and two sons, one killed beneath a grain wagon, lie buried.

We do not often acknowledge that the Oklahoma homestead became available for settlement in the first place because the U.S. Congress had passed legislation taking away “excess” land from the indigenous Cheyenne. The Cheyenne were displaced by two of the most discreditable episodes in frontier history in 1864 and 1867, and settled near the Washita. As a result, the farming district between the towns of Bessie, Cordell, and Corn was a checkerboard of Mennonite and Cheyenne land.

We know that Jacob’s nephew, Johannes Klaassen (1895–1918), who had grown up on an adjacent quarter-section, was one of the first group of three draftees from the community to report to Camp Travis in Texas. We know that he was court-martialed and sentenced to twenty-five years of hard labour at Fort Leavenworth for his anti-war views. And to his father’s great distress, he was sent home in October 1918 in a coffin, dressed in an army uniform.

We know that Jacob had already instructed his oldest sons, Jacob and Martin, to board the train in Clinton under cover of night in the direction of Canada; that relatives in Montana coached them across the border into Saskatchewan; and that Martin, my grandfather, lacking any official papers, was taken from the train in Moose Jaw to prison until his Uncle David Toews could intervene for him.

We know how war disrupts lives and disperses families.

But we also live in North America, where we are tempted to place ourselves inside the powerful settler mythology in which this continent becomes the final destination in the search for freedom—what the historian Tony Judt calls the “narrative of geographical emancipation: escaping the wrong places and finding our way to better ones.”[1] If we do so, we will be hard-pressed to imagine the anti-foreigner hysteria that was manufactured nationally and in Oklahoma in 1917 around the declaration of war.

I say “manufactured” because war and conscription were not greeted with enthusiasm in the Oklahoma countryside. In the months and years leading to 1917, rural Oklahoma had been a hotbed of political activism and agrarian radicalism.[2] There is no evidence that the Klaassen family, steadfastly apolitical, was involved in any of it, but they could not have missed the copies of the Sword of Truth newspaper or the posters in Washita County, warning landlords against mistreating tenant farmers and sharecroppers, who were a major force in organized movements to stop rent-gouging and stabilize land tenure. In this they were often supported by holiness preachers of the kind depicted in John Steinbeck’s novel, Grapes of Wrath. In the 1916 national election, the Socialist candidate for President, Eugene Debs, got one in six votes in Oklahoma and almost 40 per cent in a neighbouring county.

When war was declared, members of a loose coalition of farmers, Seminole-Muskogee and Creek peoples, recent immigrants, African Americans, and “Wobblies”—advocates of One Big Union—led a brief uprising mostly on the eastern side of the state that took its name, the Green Corn Rebellion, from a Muskogee sacred harvest ceremony. The uprising was ill-planned; its objectives were unclear. But the combination of war and rebellion provided a pretext for the political establishment in the towns to crack down indiscriminately on a much wider circle of their opponents. The state established a Council of Defense in each county, comprised of some of those leading citizens. The Councils hired thugs and vigilantes to do their most violent work.

The real war, in other words, was often a local one in Oklahoma. A farm leader in Bessie was tarred and feathered. A newspaper editor, insufficiently patriotic, was shot on the steps of the Washita County courthouse in Cordell. A church was burned. German place-names were altered (Korn to Corn); German-language schools and newspapers like the local Oklahoma Vorwärts were forced to close. By war’s end, the Ku Klux Klan was a major force across the state.

In Oklahoma in the summer of 2000, I asked our relatives about any lingering local feelings from the war. The conversation got very quiet. A woman described how, not long ago, she had been afraid to speak at work in defense of Mennonite conscientious objectors (COs) when the subject came up; her boss was connected to one of the old notable families in town. Her husband said people still avoided talking about the war in order to get along.

Oklahoma’s wartime intensity may have been exceptional, but the same popular feelings could be found throughout the Great Plains. They were amplified politically at the national level. President Woodrow Wilson, who had been re-elected in 1916, promising to keep the U.S. out of the war, also seized the moment to target so-called hyphenated Americans. He had already prepared the ground for such a campaign with these chilling comments in his Third Address to Congress in 1915: There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags, but welcomed under our generous nationalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life… The hand of our power should close over them at once.[3]

The construction of national identity is always about defining who is inside and who is outside—who is not one of us. A serious and significant intelligence report prepared at the time for the War Department identified Mennonites, Amish, and Hutterites as dangerous, unpatriotic people, communist in practice, possibly part of a pro-German conspiracy to undermine the war effort.[4] The truth didn’t matter. All members of those communities were automatically under suspicion, and often monitored by the citizen councils of defense.

At one point, close to 200 Mennonite leaders were threatened with sedition charges for signing a joint letter on the subject of war bonds; in that case the Justice Department said no. At other times, the law sided with the mob. A Mennonite pastor in Montana, for example, narrowly escaped lynching at the hands of local notables led by the sheriff. How quickly the public mood could turn—and turn against neighbours.

For President Wilson, conscription served the larger purpose of creating a unified nation. The Selective Service Act of 1917 required all able men, aged 21 to 30, to prepare for call-up. Sociologically, the war effort was a melting pot for young men drawn from immigrant enclaves, rural and urban, by the new draft lottery and sent to one of 16 large camps across the country, mostly in the West, which presumably had more recent immigrants to integrate. There they were issued the same U.S. army uniform—a word that bears reflection.

The Act made provision for conscientious objectors to choose non-combatant roles, but required them, unlike in Canada, to report as soldiers to the designated military camp if drafted and there request an alternative assignment.[5] The Act left the meaning of non-combatant service to the President to define, but no such definition had been given when the first trains filled with young men arrived at the camps.

For declared COs, the physical and verbal abuse that began on the trains continued in the camps, whose commanding officers intended to uphold military discipline by dealing resolutely with pacifists. Uncooperative COs were welcomed with repeated near-drownings, beatings, sexual humiliations involving guns and sticks, and, in at least one case, at Camp Funston in Kansas, a mock execution.[6]

The culture of permission came from the top. Despite assurances given to the Mennonite leaders who travelled to Washington, politicians who had set fire to the popular mood had little room to grant special privileges or show sympathy in public.

About three million men would report to military training camps during the course of the war. Of the three million, about 20,000 arrived in camp with CO certificates extracted from local authorities like those in Cordell. Of that number, about 4,000 continued to affirm those declarations despite intense pressure. Some chose non-combatant service, for example, in the medical corps. Some got farm furloughs.

About 450 were court-martialed and sentenced to hard labour for terms as long as 30 years for refusing to wear uniforms or perform specific duties. Among them were Mennonites, Amish, and Hutterites, but also Quakers, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Doukhobors, liberal Christians, secular Jews, socialists, anarchists, atheists—a melting pot, too. There were more court-martials at Camp Travis than anywhere else, notwithstanding the disciplinary practice of confining men for days in the stockade, without protection from heat, sun, or rain.[7]

Of those 450, at least 27 COs died in military prison. One of them, Johannes Klaassen, was the nephew of my great-grandfather, the cousin of my grandfather.

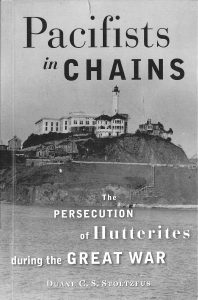

In his recent book, Pacifists in Chains: The Persecution of Hutterites During the Great War, Duane Stoltzfus gives a fascinating, troubling, and very relevant account of the targeting of the bodies and minds of young men. The book follows in close detail the story of four Hutterite men—three of them Hofer brothers—from a colony in South Dakota, who were drafted and reported to Fort Lewis, though they were married with children and might have sought exemptions. They were soon court-martialed for non-cooperation and sentenced to hard labour in Alcatraz Prison, long before it became a tourist attraction in San Francisco Bay.

In his recent book, Pacifists in Chains: The Persecution of Hutterites During the Great War, Duane Stoltzfus gives a fascinating, troubling, and very relevant account of the targeting of the bodies and minds of young men. The book follows in close detail the story of four Hutterite men—three of them Hofer brothers—from a colony in South Dakota, who were drafted and reported to Fort Lewis, though they were married with children and might have sought exemptions. They were soon court-martialed for non-cooperation and sentenced to hard labour in Alcatraz Prison, long before it became a tourist attraction in San Francisco Bay.

When the Hutterites refused uniforms and work assignments, they were confined to isolation cells in the prison basement. Dressed down to their underwear, they slept on damp concrete; they went without food for days; and in the deepest row of cells they saw no light other than what entered when the door opened. Sometimes they were manacled, hands together, to the bars above their cell doors, so high that only their toes touched the floor and their limbs ached when they were released. Sometimes they were lashed at the same time.[8]

In November 1918, just after Armistice, the four Hutterites were shipped by train from Alcatraz to Fort Leavenworth with its 40-foot walls above the Missouri River and its Special Disciplinary Barracks, where COs were housed. From the train, they were marched together, in chains, suitcase in one hand, Bibles in the other, through the streets of the town and up the hill. Though official reports later discounted it, others recalled that they ran a gauntlet of soldiers prodding them with bayonets. Finally, they stood outside on a cold November night waiting for the camp commander.[9]

The isolation and manacling resumed. Within two weeks, two Hofer brothers were dead. Their families were alerted of their failing health by telegram; their father, wives, and children arrived in time to say their farewells. One brother died that night. When his wife demanded the next morning to see his body, she found him in a coffin dressed in an army uniform. When the brother died days later, his family appealed successfully to prison officials not to dress him in a uniform for the train trip home for burial.[10]

Though we know less of what Johannes Klaassen endured at Leavenworth, all of this has a very familiar ring, as did the official cause of death: influenza. Certainly, there was a global pandemic in late 1918, helped by the disease vectors of troops moving across oceans and continents. But, as Stoltzfus notes, a place like Leavenworth presented optimal conditions for the spread of influenza: crowded, cold, damp, poorly ventilated cell-blocks, poor diets, and populations of young men, a highly susceptible demographic.[11]

In the last days of the war, Jane Addams, the Chicago campaigner for world peace, women’s suffrage, and the rights of immigrants, who won the Nobel Prize in 1931, and the National Civil Liberties Bureau, investigated conditions at Leavenworth.[12] Needless to say, these were not the sort of friends that Mennonites from Oklahoma or Hutterites from South Dakota would expect to find in the world; but then they could not look for support from the rest of Christianity—certainly not from those who had begun to call themselves fundamentalists, and not from many in the mainline Protestant denominations either.

The Bureau’s report used a blunt word, “torture,” to describe the treatment of CO prisoners. The U.S. government’s response was dismissive: these were radicals. The families received no apologies. Before the last surviving COs were released from prison in 1919 and 1920—against public demands that they should serve their full sentences—some of the Hutterite families had moved to Canada.

This is a powerful, dark story. It is our Klaassen story, too. We would not be here otherwise. The story comes from a time when it mattered a great deal to the U.S. government and all of its agents, at every level, to claim the bodies, the tongues, and the undivided loyalties of young men for a war effort it had disavowed only months before; and when that loyalty was stubbornly refused, their bodies could be abused unto death, though they represented no threat whatsoever to the national security of the United States. They had no secrets to divulge.

The story comes from a time, too, when those young men bore a disproportionate share of the burden for upholding the historic peace tradition of nonresistance that had displaced Mennonite communities to a new continent in a time of war. Conscription put them front and centre. Their own leaders had been caught unprepared by the war, the public mood, and the government’s response; they could not find a common Mennonite position. The young men often felt left to themselves to negotiate a gauntlet of abuse and propaganda. But imagine the parental and community expectations in places like the Herold Church, especially where the identity of Anabaptist Christianity was taken so seriously.

We are now far removed from the circumstances that ripped the Klaassen family out of Oklahoma. We do not worry for ourselves in that way. The daily political news on our troubled continent, however, contains plenty of distressing reminders of 1917. Our story is not just our story. For others, it is far from over.

If we remember our story, it is not hard to imagine a country and some of its noisiest political—and Christian—leaders swept up in anti-foreigner hysteria.

It is not hard to imagine people and places of worship monitored and attacked simply because of the religious identities they represent. Surely, they must be connected to the international enemy.

It is not hard to imagine that recent immigrants can get reported and arrested for speaking in their first language in public—say, in an airport lounge—even if they are expressing everyday things, or holy things. If they want to avoid suspicion, they should speak English!

Let me risk one more step. The more I have learned about the events of 1917 and 1918, especially about the treatment of COs in American military prisons, the more I am struck by the echoes in what has happened more recently at Abu Ghraib in Iraq and at Guantanamo naval base, which was chosen, in fact, over Leavenworth as the place to house prisoners swept up in an indiscriminate global dragnet after 9/11; for it was thought to be beyond reach of either international or domestic law. I am not suggesting exact parallels here. But the culture of permission was much the same. So was the enlistment of rank-and-file soldiers in a familiar catalogue of cruelties: isolation, exposure, sexual humiliation, simulated drownings, manacling.[13] The prisoners were less than human. They deserved what they got.

My point is that if we are true to our Klaassen story, then we also know enough to refuse enlistment in the political campaigns that now swirl around us—the campaigns that give permission, that draw hard lines between those inside and those outside. For we have been outsiders longer than not. We have felt the hand of power, in those chilling words, close over us. That is the story we know. That is why we are here. Let it not happen to others.

Written by Roger Epp, a professor of Political Science at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. This article is adapted from a talk he gave at a Klaassen family gathering in Saskatchewan on August 6, 2016. The article was first published in the March 2017 issue of Mennonite Historical Society of Alberta newsletter. It was reprinted with permission in Mennonite Historian 43/4 (December 2017): 1, 4-5, and 8.

Notes

1. Judt is describing the various east-to-west migrations of his own Jewish family (Tony Judt, with Timothy Snyder, Thinking the Twentieth Century [New York: Penguin, 2012], 24).

2. In these paragraphs, I am drawing partly on what I have written in We Are All Treaty: Prairie Essays (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2008), especially chapter 6, and on the historical sources indicated there.

3. Woodrow Wilson, Third Annual Message to Congress, December 7, 1915, The American Presidency Project, at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29556.

4. See Allan Teichrow, “Military Surveillance of Mennonites in World War I,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 53 (1979): 95–127; and “World War I and the Mennonite Migration to Canada to Avoid the Draft,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 45 (1971): 219–249. In the latter article, Teichrow writes: “For a man of German ancestry who happened also to be a conscientious objector, America was in some ways the worst of all possible places in 1917–18” (pp. 227-28), especially Oklahoma, where “mob violence . . . always lurked beneath the surface” (p. 246). He notes that Mennonite group emigration was greatest from Oklahoma.

5. Duane Stoltzfus, Pacifists in Chains: The Persecution of Hutterites during the Great War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), provides a very good recent overview of the circumstances in which Mennonites as well found themselves. See also Melanie Springer Mock, Writing Peace: The Unheard Voices of Great War Mennonite Objectors (Telford, PA: Pandora Press, 2003); Gerlof Horman, American Mennonites and the Great War: 1914–1918 (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1994); James C. Juhnke, “Mennonites in Militarist America: Some Consequences of World War I,” in Kingdom, Cross, and Community: Essays on Mennonite Themes in Honor of Guy F Hershberger, eds. J. R. Burkholder and Calvin W. Redekop (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1976); and Mary Ellen Snodgrass, Civil Disobedience: An Encyclopedic History of Dissidence in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2009), 195–197. Three valuable online sources of documents and oral histories are the Bethel College Library World War I Oral History Collection at https://mla.bethelks.edu/ww1.html; the Swarthmore College Peace Collection at https://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/conscientiousobjection/co%20website/pages/HistoryNew.htm; and the Home Before the Leaves Fall Project at https://wwionline.org/introduction.

6. Stolztfus, Pacifists in Chains, 36–38.

7. The Bethel Oral History Collection contains an interview with Peter Quiring, who had enlisted with Johannes Klaassen from the Herold Church and whose family had also been on the trek to Central Asia. The audio files are available at https://mla.bethelks.edu/audio/ohww1/quiring_peter_j1.mp3 and https://mla.bethelks.edu/audio/ohww1/quiring_peter_j2.mp3. See also John W. Arn, The Herold Mennonite Church, 1899–1969 (Newton, KS: Mennonite Press, 1969), which provides local details of the war at pp. 13–17. Transcripts from the court-martial of a Quaker CO at Camp Travis can be found at http://civilianpublicservice.org/sites/civilianpublicservice.org/files/HarryLCharles.pdf.

8. Stolztfus, Pacifists in Chains, 117–121.

9. Stoltzfus, Pacifists in Chains, 159–161.

10. Stoltzfus, Pacifists in Chains, 172–174.

11. Stoltzfus, Pacifists in Chains, 174–175.

12. Stoltzfus, Pacifists in Chains, chapter 8. The NCLB report by David Eichel was released in December 1918 under the title What Happens in Military Prisons: The Public is Entitled to the Facts.

13. Confidential reports prepared by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and leaked to newspapers in 2004, for example, identified the use “humiliating acts, solitary confinement, temperature extremes, use of forced positions”—each “a form of torture”—against prisoners at Guantanamo, as well as similar abuses at US military prisons in Iraq. See Neil Lewis, “Red Cross Finds Detainee Abuse in Guantanamo,” New York Times, November 30, 2004, at http://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/30/politics/red-cross-finds-detainee-abuse-in-guantanamo.html; and “Red Cross report details alleged Iraq abuses,” The Guardian, May 10, 2004, at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/may/10/military.usa.

Canada 150: On track? or derailed?

Posted on September by Jon Isaak

CPR logo from the 1890s

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) saved my people’s life. Maybe that sounds a bit dramatic. And actually, it’s a bit strange to say it that way—I don’t really ever talk about “my people” quite like that. But for this particular story, I’m learning it’s important that I do. Indeed, for many of us, this story is as familiar and formative as the biblical story of the Exodus itself.

The particular story is this: a century ago, as World War I was grinding on and the Russian revolution flared up, “my people” (those Mennonites of Dutch descent who spoke German and had lived as colonists in Russian-conquered Tatar, Bashkir, Nogai, and Ukrainian territories) experienced incredible hardship. Mennonites in North America heard about the hardships, and responded generously with relief supplies.

But many of the Mennonites from Russia wanted more than aid; they wanted to emigrate. They investigated US, Canada, and Mexico as possible destinations; only Canada chose to open its doors. But as a plundered and war-ravaged people, the costs of emigration were prohibitive. In 1922, a group of leaders formed the “Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization” and signed a deal with the CPR to transport 3,000 refugees on credit.

The émigrés began arriving in 1923, and by 1930 the CPR had brought more than 21 thousand refugees to Canada, at a loaned cost of over 1.7 million dollars. The stories of those left behind (like my father-in-law, who escaped the Soviet regime during World War II, or others who left for Germany in the 1970s, or who like my father’s half-sister outlived the USSR and could be visited by Westerners in the 1990s) reaffirmed the reasons to be thankful for the CPR’s way of escape.

In the minds of many, the CPR was a divine tool along the lines of biblical Cyrus, God’s “anointed” who brought release to Israel in exile.

The CPR destroyed my neighbours’ lives. Again, this is perhaps overly dramatic—but in the bigger picture, I don’t think so. Railway was the Next Big Thing in the mid 1800s. And as the railways came westward first across the American Midwest, then in copy-cat style a generation later north of the 49th, they led to the catastrophic demise of the American bison, the mainstay of the prairie First Nations economies. This happened indirectly, by slicing up the seasonal paths of the grazing herds; but also more directly, by importing hunters by the thousands, and transporting out bison skins by the hundreds of thousands (one firm in St. Louis traded a quarter million hides in 1871).

We know the economic pain of crude oil dropping from $100 to $40 a barrel; can we imagine the devastation and cultural upheaval of the total collapse of the bison economy? Herds numbering in the tens of millions at the time of colonial contact were reduced to a few isolated remnants totalling about a thousand animals by 1889. The resulting mass starvation on the prairies became a very useful tool in the hands of the colonial governments, to encourage bands to sign the treaties—treaties that laid the groundwork for the colonizing that brought my people to Canada.

The CPR saved my family’s life. My own family is bound up very much in the CPR immigration story. As the poor refugees arrived in Canada full of hope (including my mother’s Thiessen family in 1925, and my father’s in late 1928), the Great Depression struck. The $1.7 million debt looked like an impossible burden. And my grandfather was the chief debt collector for the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization, as an employee for the CPR. C.F. Klassen criss-crossed the country (by train, of course), visiting every little Mennonite church, farm, and house, collecting dollar by dollar, sometimes only penny by penny, the prohibitive debt.

The principal was paid off in 1946; only $180,000 had been paid in interest, and the CPR forgave another $1.5 million in interest. How could this not be seen as God’s grace? And this work paved the way for another work of grace, as my grandfather returned to Europe after the war, and directed the resettlement of over seven thousand more Mennonite refugees from the USSR. His CPR work gave him knowledge of hundreds of Mennonite homes and communities across Canada, so that when he met fleeing families in Europe, he could help to connect them to relatives across the Atlantic.

The CPR derailed my neighbours’ families. The story of the building of Canada “from sea to sea” is the story of the railway, and the CPR in particular, as the reward promised to British Columbia for joining Confederation. It’s the story of “opening up” the West to European settlers, to occupy land advertised as “empty.”

It’s very specifically the story of the Riel Rebellion, with its almost 3,000 Canadian troops shipped out from Ontario and east, via the just-finished CPR lines, to suppress the Métis uprising against Ottawa’s unjust rule. The fear that this event fomented in eastern Canada of “savage Indians” was then used to tighten the already oppressive regime of the Indian Act. For example, the unofficial (never passed into law) policy of the pass system was still enforced, restricting the movements of Indigenous peoples off reserve.

And then, in 1890, Mennonite settlers arrived by rail in Laird, Saskatchewan. Federal agents in the years following sold those settlers land that had been set aside for the Young Chippewayan First Nation (Reserve 107). These Cree had signed Treaty 6 in 1876, but had fled the region in the aftermath of government crackdowns because of the 1885 Métis uprising (as well as on-going famine because of the disappearance of the bison).

The land was theirs, but vacant, and now it was illegally re-appropriated and sold to settlers from “my people.” The Young Chippewayan band, disbanded for a century and spread across western Canada, continues to work today to convince the government that they are the legitimate heirs of that broken treaty promise.

These intertwining stories are just a tiny, personal slice of 150 years of Canadian colonial complexity. It’s not a rant or an attack on the railway per se, although the CPR was certainly a tool and a promoter of the larger project of colonialism (and it’s commonly acknowledged that the railway enterprise of Canada’s nation-building era was an “orgy of corruption”: political kickbacks, subsidies, and the like). But mostly, this is a lament for the inextricable link between my story and my neighbours’ stories, to which I’ve been blind for most of my fifty-plus years.

It’s a painful reminder that as much as the CPR is part of my family’s story, I am also part of the CPR’s deeply checkered story. I might paraphrase the apostle: “The very railway that promised life [to me] proved to be death [to my neighbour]… Did that which is good, then, bring death to me? …Wretched colonial that I am! Who will deliver me from this body politic of death?”

Who indeed! There is a Person whose name is Truth. And his mission in life (and death) is Reconciliation, a journey which he calls us all to join him on. For me, that has meant a willingness to have my eyes opened to the existence of my Indigenous neighbours. Very specifically, the lives of Cree neighbours like Junior, Lucille, Kohkom Betsy, Jamin, Shelley, Hal, Margaret, Moshom Charlie (may he rest in peace), and other friends. People whose lives and lands have been subject to the derailing actions of a century and more of Canadian injustice, yet who remain people of generosity, goodwill, wisdom, and good humour. Their friendship invites and inspires me to get to know their story better—and to let it shape my own.

I look forward to a time in Canada when their people and mine, indigenous and settlers, can all live side by side with openness, trust, and friendship. Side by side, strong and true, like parallel ribbons of steel, equal in size, stretching across this vast land—no, stronger yet, strong like the solid earth beneath the rails, the ground on which all else is built.

Written by Randy Klassen. Randy lives in Saskatoon, in Treaty Six territory. He works for MCC Canada as national restorative justice coordinator. This article appeared in Mennonite Historian 43/3 (September 2017): 5 and was based on an earlier version appearing online as a blog post at <www.newleafnetwork.ca>.

PhD Student Saves History from the Shredder

When Jeremy Wiebe heard that the remaining inventory of Mennonites in Canada (volumes 1–3) were in danger of being shredded to save warehouse storage fees, he took action. Using his computer programming skills, and the offer of the Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies to take care of transportation to Winnipeg, storage, and shipping, PhD student Wiebe established a webstore at www.mennonitesincanada.ca with e-commerce capabilities that went live on April 12, 2017.

Wiebe’s idea was pitched at the January 2017 meeting in Winnipeg of the Mennonite Historical Society of Canada. The Society had been looking for a way to sell its remaining copies of Mennonites in Canada volumes. A liquidation price of $5 per book, or $15 for the set of three meant that MHSC would get at least some return for these valuable books; and CMBS agreed to handle the shipping to anywhere in Canada for $20.

Sales have been brisk, according to Jon Isaak of the Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies. “We are down to only a few copies of volume 1, with more of volumes 2 and 3 remaining.” Isaak noted that some people are buying 15 books at a time to give as gifts.

The three volumes—1,500 pages in total—are widely recognized as the definitive history of the Mennonite experience in Canada from 1786 to 1970. The first two volumes, published in 1974 and 1982, were authored by Frank H. Epp; and the third volume was written by Ted Regehr and published in 1996.

Wiebe, a Mennonite history student in graduate studies at the University of Waterloo, is not surprised by the response. “An entire generation has come of book-buying age since the last volume was published,” Wiebe noted. “It would be a shame to see the books destroyed when there are people who would be thrilled to own this history of the Mennonite experience,” he continued.

The subtitles of the books show a progression: from “A history of a separate people,” then to “A People’s Struggle for survival,” and onward to “A People transformed.” Today Mennonites can be found in virtually all corners of Canada, some seeking to remain a separate people, others embracing the diversity of what the world offers, and still others finding their identity at some point on the separation-assimilation spectrum.

To order your copies, visit www.mennonitesincanada.ca; for orders outside of Canada, email cmbs@mbchurches.ca for a quote on shipping costs.

Written by Conrad Stoesz. This article appears in Mennonite Historian 43/2 (June 2017): 7. See complete collection of Mennonite Historian archived on the magazine’s website, http://www.mennonitehistorian.ca

Mennonite Family History Workshop on May 6 @ CMBS

• Get tips on researching your roots.

• Hear about heritage tours to Poland, Russia/Ukraine, and Europe.

• Learn about the archives and how to use them.

Presentations by Dr. Glenn Penner and Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies archivist Conrad Stoesz.

Suggested donation of $20 supports the Centre for MB Studies. Refreshments included.

McIvor Ave. MB Church Beginnings

Posted on by Jon Isaak

North Kildonan Mennonite Brethren (NKMB) church in Winnipeg at 217 Kingsford Ave. had two problems in 1974: the church building was too small to accommodate the weekly attendance and many people in the congregation needed an all-English service.

At the time, the worship services in NKMB were an hour and a half: the first hour was in English, followed by half an hour in German. Typically, there would be a large exodus when the German service was about to start by people who did not understand German or who felt that one sermon was enough for one Sunday. The commotion was covered by providing what came to be known as the “organ break,” which functioned as a transition into the German half hour of songs and sermon.

It was decided that NKMB would build a new church. Church member and businessman Henry Redekopp had land on McIvor Ave., which he donated to the project. A building committee was struck. Another member, architect Helmut Peters, was commissioned to draw up a design. The building would cost $500,000 and construction would begin as soon as $200,000 was raised in cash and pledges.

The identity and number of people who would comprise the new congregation remained unknown and the construction was undertaken by the still-undivided NKMB church. Whichever congregation was smaller, the all-English or the bilingual, would become the congregation of the new church building, thus solving the dual problem of overcrowding and the unpopular exodus during the organ break. The projected completion date was the end of September, 1976.

Pastor William Neufeld and Assistant Pastor Allan Labun approached the church council with the observation that there would not be one new church, but two, and that consequently they would both be out of a job. The council agreed and proposed to the church that Pastor Neufeld be the pastor of the remaining members of a bilingual NKMB church and that Pastor Labun be appointed to the new all-English church. The proposal was accepted.

In July, letters were sent out to all 750 members, stating that a new all-English church with Allan Labun as pastor was being established. Any members of NKMB who wished to become part of the new church should sign and return a tear-off slip at the bottom of the letter. All others need not reply and would remain as members of NKMB by default. The specific church building in which each one would meet would depend on numbers. The cutoff date for a reply was the end of August, 1976. By the end of August, responses had been received from 248 members, almost exactly one-third of the church membership. This group, being the smaller, would move to the new building.

Allan Labun promptly announced a membership meeting of the new church two weeks into September, to be held in the basement of NKMB church. The new church had a building, 248 members, and a pastor, but nothing else: no name, no council, no Sunday School, not even pews or any other seats to sit on. People walked into the meeting and eagerly picked up the membership lists, looking around to see for the first time who they would be worshiping with. Those were exciting and heady days for us. The first item on the agenda was to elect a recording secretary (Frank Penner), then we went on to join the Mennonite Brethren Church of Manitoba, elect a moderator (Harry Olfert), a council, adopt a constitution (that of NKMB, for the time being), a Sunday School Superintendent (Abe Reimer, who by the end of the evening had already recruited half his Sunday School teachers). We began talking about a name, a matter that was not settled until another meeting the following week.

The church dedication was carried out on October 10 by NKMB, the mother church, in the new building. About 800 people squeezed in for the event, sitting on borrowed stacking chairs. Our first independent service was held on October 17, 1976.

The final cost of the new building came in at $525,000 and at the time of the dedication there was still an outstanding debt of $122,000. This is quite amazing considering that no one knew who would occupy this new building until two months prior to dedication.

The question of the remaining $122,000 was addressed by a joint committee of the two churches. The committee proposal was that NK accept $35,000 and McIvor Ave. would accept the remaining debt of $97,000. The proposal was voted on and accepted by each church.

Written by Allan Labun, Harry Olfert, and Clara Toews. This article was first published in Mennonite Historian 42/4 (December 2016): 7. See complete collection of Mennonite Historian archived on the magazine’s website, http://www.mennonitehistorian.ca

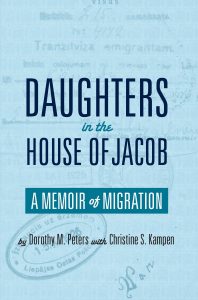

Daughters in the House of Jacob

This new publication is a memoir of migration, written by two Canadian Mennonite women—a Bible professor and a pastor. It traces their vocational calling across generations and gender, back to their Bible teaching-preaching grandfather Jacob and to their unforgettable great-grandmother Agatha. The authors interview elder-storytellers and investigate leads through a trail of letters, pictures, and documents, while reflecting on their own journeys and solving a few mysteries along the way.

This new publication is a memoir of migration, written by two Canadian Mennonite women—a Bible professor and a pastor. It traces their vocational calling across generations and gender, back to their Bible teaching-preaching grandfather Jacob and to their unforgettable great-grandmother Agatha. The authors interview elder-storytellers and investigate leads through a trail of letters, pictures, and documents, while reflecting on their own journeys and solving a few mysteries along the way.

Dorothy M. Peters divides her time between writing and hospitality on Mayne Island, British Columbia, and teaching and lecturing on the Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Christine S. Kampen serves as a pastor at Highland Community (Mennonite Brethren) Church in Abbotsford, British Columbia.

What are reviewers saying about the book?

“Warmly, and with astonishing honesty, cousins Dorothy Peters and Christine Kampen relate ‘who we are’ as women with a God-call to ministry. They draw us into the ‘surprises, secrets, and treasures’ of their wonderfully complicated family saga.”

–Dora Dueck, author of This Hidden Thing and What You Get at Home

“Peters and Kampen model what it means to come to different conclusions than parents and still remain within a wholesome family dynamic.”

–Patricia Janzen Loewen, Providence University College, Otterburne, Manitoba

“With storyteller’s skill, Peters and Kampen bring an informative window into the sorrows and joys experienced by women whose gifts were not always appreciated or endorsed by a largely patriarchal church culture.”

–Myron A. Penner, Trinity Western University, Langley, British Columbia

Christine Kampen (left) and Dorothy Peters (right) read selections from their new book Daughters in the House of Jacob: A Memoir of Migration, during the book’s launch on June 4, 2016, at the Mennonite Heritage Museum in Abbotsford.

The book is a publication of the Mennonite Brethren Historical Commission and Kindred Productions.

To order your copy, visit the Kindred Productions website; click here.

Released June 2016

ISBN: 978-1-894791-46-5

275pp.

Retail $22.95 CAD (plus taxes)

paperback

Mennonite Archival Image Database (MAID) grows

Posted on by Jon Isaak

Anna and Peter Ediger with their children Anna, Peter, and Martha on their farm in Escondido, California

The Mennonite Archival Image Database (MAID) is growing and with it, extending its reach for people looking for rare images. On the eve of its first anniversary, MAID welcomes the Mennonite Library & Archives (ML&A) at Fresno Pacific University (Fresno, California) as our newest archival partner.

ML&A is the eighth MAID partner and the first outside Canada, which enhances MAID’s vision of being a source for “the discovery of photographs of Mennonite life from around the world.” MAID’s eight partners have now collectively uploaded over 82,000 photographic descriptions into our Internet-accessible database (http://archives.mhsc.ca); nearly 19,000 of these have scanned images attached.

With each new partner, the Mennonite family and network becomes larger and stronger. Archival photo experts from each centre help provide valuable information about photos in their own collection and collaborate with other partners improving the contextual knowledge of various collections, benefiting everyone. Over time, and as families and their records scatter, information becomes lost.

However, as photo experts work at posting and describing photos, connections between photos that are held in different archives are found. It is not uncommon for two, three, or four archivists to be in discussion on a series of photos. Each archivist can supply important pieces of the puzzle that brings us collectively closer to identifying a photo or people in the photo. Each archivist has long-standing knowledge and networks that can be tapped to help identify people, places, and events. Through the collaborative network of MAID and its partners, the Mennonite community of yesterday is slowly being reconstituted.

ML&A has begun entering photographs into MAID from its rich collections, which consists of tens of thousands of photographs. Highlights include the Henry J. Wiens photographs of Mennonite Brethren church buildings, photographs of Mennonite Brethren congregational life on the west coast of the United States, the Fresno Pacific University photograph collection, and a massive collection of Mennonite Brethren mission photographs from around the world. Kevin Enns-Rempel (library director) and Hannah Keeney (archivist) are coordinating photograph entries from Fresno, which involves selecting images and providing the descriptions that will make them searchable on the Internet. “These photographs have been available in the archives for many years, but only to those researchers able to visit the archives,” says Enns-Rempel. “MAID will make these photographs visible to the world, and will spur interest in the larger archival collections at Fresno.”

Attendees at the 1947 Southern District Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches in Fairview, Oklahoma. Henry J. Wiens photograph collection, Mennonite Library and Archives, Fresno, CA.

The Mennonite Library and Archives is one of four North American archival centres for the Mennonite Brethren church in North America. It is located in the Hiebert Library at Fresno Pacific University. The archives hold records of the Pacific District Conference of the Mennonite Brethren Church, Mennonite Brethren Biblical Seminary, the General Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches, Fresno Pacific University, and personal manuscript collections related to the Mennonite Brethren church. In addition to the archival collections, the ML&A also holds an Anabaptist/Mennonite library collection of nearly 17,000 volumes.